What I Thought of the Book

A Summary of the Book

A Timeline of Dates from the Book

Lingering Questions

Conclusions Drawn as they Relate to Bluegrass

If you only read one thing read the conclusion. That's the whole point of this blog. For the next post, I'll try to make the conclusion longer and the summary brief. The timeline is also pretty neat and it took me a long time so it would make me feel better to know someone looked at it. Please feel free to comment on this post and tell me how right or wrong you think I am. I also highly encourage you to please share this with anyone who you think will enjoy it. I'm low key trying to build a network of people who will correct me all of the time but its in your best interest to help me because then you'll know too (see "jam nuggets"). Also, it was just or will soon be my birthday! Consider donating as a way to support this blog if you like what your read!

Thanks so much for checking this out I'm excited to share this stuff with you!

The Book

That Half-Barbaric Twang is a book about the history of the banjo in American pop culture. Written by Karen Linn, an archivist in the Manuscript Division of the Library of Congress, this book was published in 1994 so I think some of the information in the book has become a little more common knowledge since it was published. I knew about Joel Walker Sweeney adding a string but not the short string, I was aware of the banjo's tie to minstrelsy, and I had seen Throw Down Your Heart so I was aware of its African roots but I really had no idea how point A connected to point B. This is a very thorough and well-researched book that went to great effort to really trace the path of the banjo through American history and pop culture. It provides really wonderfully thought-provoking and well-documented arguments for why certain feelings about the banjo exist today which was exactly what I was looking for. Reading this book I was hoping to find some sort of reasoning behind people's prejudices and common reactions to the banjo today and I think the book presents some interesting information on this topic.

I found this book to be a really helpful resource. I obviously came to it from a bluegrass perspective and judging from many of the reviews online, so did a lot of other people. Unfortunately for people whose interest lies only in bluegrass or old-time banjo, this is not a particularly light read and only one chapter "Southern White Banjo" talks about either of these things. For those generally interested in history and the cultural history of music, though, this book is great. The writing is academic (dry) but contains so much well-researched information that it manages to stay interesting. The book deals a lot with race issues and history and occasionally it felt like the author was pushing an agenda but very rarely and never enough to detract from the text. The only part I have trouble with was the epilog where the author talks about a personal experience at a Smithsonian Folkways festival where she takes some of the borderline offensive and appropriating shows of a folk-based old time festival, and ties the blame in with bluegrass. No one is playing bones on stage at a bluegrass festival. Despite the book having been written a quarter of a century ago, it actually still holds up pretty well. I don't think there have been any particularly radical changes to the banjo and how people perceive it since the early 90's. (I know about country music but what I'm saying is rather than the banjo shifting in meaning country music shifted its image to be more sentimental and less highbrow and, oh look the banjo is suddenly back).

There are some very heavy topics in the book that made writing this summary very difficult. Race and Class relations are a tricky subject to begin with but when put through the lens of the banjo and written for the consumption of a community as diverse as bluegrass well it gets downright intimidating. The book doesn't go into too much detail about either of these things directly and instead lets the events of the past paint a picture of the reality. I try to do the same in my summary.

If this book sounds like something you'd be interested in I'd suggest you support the author and get yourself a copy!

What Was the Book About?

The banjo as we know it today is a decedent of an African instrument originally brought to America by the slaves. Banjos had been mentioned in fiction and stories of the South enough that by 1810, mentions of the banjo in literature apparently no longer warranted a description of the instrument. While the banjo was played by black Southerners, working class whites in both the North and South were also playing the banjo as early as 1857. Throughout history, the banjo has gone through many cosmetic changes. One of the most important was in the 1820's when a man named Joel Walker Sweeney added a fifth string to the banjo. For a long time, it was believed that Sweeney had invented the shorter string on the banjo that is (confusingly) referred to as the "fifth string". Paintings that predate Sweeney's life showing the shortened string disprove this theory. Sweeney most likely added the lower bass string which is now commonly tuned to a D note. Throughout the rest of this half of the century, blackface also starts to show up as a popular part of the circus culminating in 1843 when the first full-length blackface minstrel show is presented in New York by the Virginia Minstrels. Blackface minstrelsy is a form of theater where predominately white performers would wear dark makeup to represent black people in performances that were often meant to portray African American life and culture. The banjo was frequently if not almost always involved in blackface performances as it gave these actors an authenticity to their audiences. The banjo was at this point recognized, if not as an African instrument, then at least as an exotic instrument and made these portrayals of other cultures seem more authentic. These acts firmly set the idea of the black banjo player in the collective consciousness of the country. The representations however were, predictably, racist and inaccurate and often portrayed a skewed, romanticized view of both Southern lifestyles and the life of slaves. For this reason, minstrel shows were not nearly as popular in the South as they were in the North. The people living in the areas that these shows overly romanticized could see the blatant inaccuracies and were unaffected by their sentimental nature.The reality of Southern black culture was heavily misrepresented. While black slaves did play the banjo, just as many, if not more played the fiddle. The fiddle(/violin), however, was already associated with classical music and high art and therefore was not a suitable symbol to use to represent slaves. (It should go without saying that slaves were generally thought to be less than human and therefore unable to create viable art). In addition to misrepresenting cultural symbols, song lyrics and writing styles were written to support racial stereotypes. Minstrel songs were often written by Northern whites with lyrics meant to appeal to sentimental Northern audiences. Stephen Foster is an excellent example of this. Foster wrote songs with "characteristic" lyrics with many mentions of longing for "massa" (master) and home. These lyrics were extremely popular in their time and largely outshined less specifically romanticized lyrics. The stylized pattern of longing for home or mother's embrace and generally romanticizing the "good 'ol days" is recognizable not just in Foster's songs but in many of the American folk songs that followed them. This is partly due to Foster's songs being mistaken for authentic spirituals during the folk revival of the mid-twentieth century.

The romantic view of slavery (and by extension, of The South) in the United States is represented by this political cartoon from 1850 Boston that compares the soul crushing slavery of industrial England to the carefree lifestyle of black slaves in the wild South. When slavery was abolished, this view of African Americans as simple and wild still didn't change much and the banjo remained a symbol of their perceived inherent "barbaric" or "natural" nature. We can see from minstrel stagings of shows like Uncle Tom's Cabin that Northerners believed Southern blacks to be content with a life of servitude and to be a naturally jovial people. Tellingly, although the banjo is never mentioned in the original book, written by Harriet Beecher Stowe, stagings almost always included a banjo. Banjo playing at this point is heavily associated with young black Southern boys. After the Civil War (1861-1865) ended, it's presumed that Union soldiers would have returned with a greater knowledge of the banjo and other musical traditions of the South. The ideas perpetuated by the minstrel stage were so strongly set in people's minds that people would become very upset whenever evidence that contradict these ideas were presented. Still, we start to see a rise in interest in the banjo outside of the minstrel stage and as we enter the 1860's amateur banjoists are plotting to bring the banjo into the world of high-class art.

Banjo "elevationists" were pretty enthusiastic about the banjo and thought that this crude instrument (that's African roots gave it's existence meaning) when put in the hands of a more "rational" (read as: "white") player could make music as good as the music enjoyed by the upper class. At this point in time, the banjo is still seen as low-class entertainment with both black people and the theater. So these elevationists embark on a mission to rebrand the instrument in a way suitable to upper-class society. Violins were (and still are) generally marketed based on either how old they were or how old seeming they are. The banjo, on the other hand, has to take on a sleek modern image. The heritage of the violin is associated with very classy things such Italy and France whereas the African banjo is often depicted as practically a part of nature itself. There starts to be a lot of experimenting with banjo production both in aesthetics and functionality. Banjos with frets, banjos with machined metal parts, banjos with resonators, banjos with a completely unnecessary number of brackets, banjos with fewer strings, banjos with longer necks and banjos with modern sounding names like the "Electric Banjo" (which was not amplified. electricity was just pretty hip). Previously, banjos were made to look purposefully crude (and therefore "authentic" to their roots), start to have a complete excess of brackets and metal parts. This new modern banjo tries to take on new associations and is now often marketed with an appeal to patriotism: The Only American Instrument.

In addition to changing the look of the banjo, the banjo had to be played by different, classier people instead of just actors and black people. As it would happen, the Victorian era was coming to a close and the role of women in society was starting to change. A woman from California named Carlotta Crabtree starts performing a show on broadway which is known for breaking down cultural barriers associated with women. Her show becomes popular in the mid-1860's and the act includes her playing the banjo. This works out well for those trying to elevate the banjo as it's a gateway for them to introduce the banjo to upper-class women. As women start to redefine their role in society by changing how they dress and act, they also take up the banjo. It's important to note though that the music being played by these upper-class women is not that much different from what they might have heard on the minstrel stage. Despite the timeframe and new class association the music being played on the banjo is simply popular music. The only thing that has shifted to bring the banjo into the high class is who was playing it. There really isn't much "classical music" (western European art music. orchestras and symphonies and what not) being played on the banjo in the 19th century. The one notable exception being A.A. Farland who was somewhat of a virtuoso. Farland was also hoping to elevate the banjo and intended to do so by playing extremely complex classical pieces on the banjo. (It's interesting to note that, as far as the book talks about, this is the first time someone is using a three-finger style on the banjo. prior to this, the technique was similar to what we now call clawhammer). Still, while impressive, Farland's act is largely seen as novel and doesn't really convince anyone of the artistic merits of the banjo. The elevation will prove to have more to do with people than with music and even more to do with social value systems.

As young high society women start to play the banjo, we start to see popular images depicting a different kind of banjo romanticism. In addition to the new association with young women, we also start to see collegiate men playing the banjo. At the turn of the century, many of the top schools in the country start to have banjo clubs with students playing banjo in a quasi-orchestra fashion. A few years earlier a mandolin craze starts after a group from Spain called The Spanish Students (or Estudiantes Espanola) put on an extremely popular show in New York City playing bandurrias which were confused for mandolins. Fretted instruments, in general, are becoming popular and clubs start to pop up in towns all over the country. Magazines for these interests are created to cater to interests in both the United States and England. It would appear that the banjo was now a part of pop culture but was it truly a part of high society?

|

| http://www.thebanjoproject.org/about.html |

While the banjo appeared to be getting the respect that the elevationists thought it should, in reality, it was more of a fad for sentimental expression in an era of changing values. The elevationists, blinded by their enthusiasm, didn't seem to realize that even though upper-class people were playing the banjo, their thoughts about it had not changed. For them, the banjo still represented this exoticism and vague danger related to black people. The young men and women playing the banjo were using it to express sentimental values in a safe way that was acceptable outside of official values. Young women could start to express their newfound independence and young men were acting out rebellious tendencies by playing the banjo (it's important to understand that music in college was much different than it is today. These aforementioned college stringed instrument clubs exists solely as extracurricular activities and were seen as an acceptable expression of youth that existed outside of the official values of being in college). Society at best now saw the banjo as a youthful expression of independence but still expected its members to grow and continue on with official values. Ironically, even the banjo teachers (grown men mostly) who were closer to high society than ever who made a living teaching these young women were thought of poorly for their continued association with the instrument into adulthood.

The word "sentimental" is thrown around a lot in the book. This book doesn't thoroughly explain social hierarchies but through the texts, it shows examples of what this means. I interpret this to be essentially the prevailing feeling behind those memes you see on Facebook that heavily romanticize the past, ignoring all of the context of that time period to create the idea of utopian era that's just out of reach. In my life, I remember experiencing it a lot in high school with girls reading The Great Gatsby and romanticizing the 20's, a time full of money and extravagant wealth but also of terrible work conditions, racism and an impending economic doom. A bit of selective memory. So to understand the actions and justifications for young collegiate men playing the banjo, we have to understand that the official culture and sentimental culture exist as different sides of the same coin. These banjo players are using this symbol of the past to express longing for this utopian idea while still carrying on their lives in the official culture.

The unique sound and construction of the banjo within the American idiom makes it a great symbol for "The Other" or in other words the exotic. The exotic is often appealing because it often represents a far away land that is easy to romanticize. These views can be seen in the overly romantic portrayals of say Paris or of the "Far East". In America, we have two frequent local expressions of this romanticism; the South and the west. The history of the Wild West is, unsurprisingly, pretty horrifying. The public image of the west, however, especially at this time, was, first of all, extremely white-washed but also an image of a new land, wild, ready to have something new created. Western romanticism often plays on the idea of living "free" and being able to start from scratch. Southern romanticism on the other hand often played on romanticized images of the past. Steamboats drifting lazily down rivers, Southern belles and gentlemen, mint juleps on the porch and happy simple slaves. Whereas the West was a new life and world waiting to be tamed, the South was a veritable utopia of the "good ol days" preserved in stasis. The fact that these ideas were heavily romanticized and generally inaccurate did not matter so much as most people would most likely never get the chance to experience these worlds. These ideas existed as a comforting image to long for while acting within the rules of society. Minstrel shows and popular fiction of the time often depicted and reinforced these values creating "nostalgia for a past that never existed".

As time went on and the pre-war South was drifted further into the past, these symbols of nostalgia became outdated. By the turn of the century, minstrel shows have lost their dominance in the entertainment industry. What's most fascinating to me is that while depictions of black Southern banjo players were still being created, the very idea of the black Southern banjo player had aged in the collective consciousness. Whereas we had started out mostly only seeing depictions young black Southern boys playing the banjo we now see depictions of aging black men returning to the South and finding the banjo again as if the very idea of the Southern black banjo player had aged. The nostalgia for the past still existed but now those symbols from the past were starting directly threaten the status quo of the high class. As urban culture was on the rise and jazz was beginning to catch on, the official culture found itself at odds with the new rising popular culture. This is the end of the elevation movement. There is no hope for the banjo to be associated with the high class after this point. Their tolerance for it existed only "when black music was a safe and exotic Southern exotic folk expression rather than a commercially successful product of African American urban culture".

In the 1910's we see a dance fad emerge as proto-jazz begins to appear. What's interesting is that both the upper and working class are really taken by this craze but sentiments at this time reveal a bias based on race and class. Moral critics were quick to abhor this new dancing seen as unfashionable (think Dirty Dancing but 70 years earlier) that was heavily associated with African Americans. However, the tango was the most popular dance of high-class America in 1914. The tango is a partner dance style with (generally) sexual overtones formed in Argentina in lower-class districts of Buenos Aires. Upper-class America explained this away by claiming to have learned the reformed style from Parisians who had also recently been taken by the style, therefore making it classier (there are also a lot more white people in France than in Brazil). Even though the banjo would never be considered high class, all this dancing was a big opportunity for the banjo and banjo players. At this time we see a shift in how the banjo is marketed. Now, rather than being marketed as a leisure instrument for the high class, we see it being sold as a tool for young working class men hoping to make money and maybe raise their social status playing dance music for the elite.

Still primarily a rhythm instrument at this time, the banjo worked great in dance bands of all styles. The work of people like S.S. Stewart (remember the fancy non-electric "electric banjo"?) and other people trying to elevate the banjo suddenly comes to fruition in an unexpected way. While banjo makers were unsuccessful in re-associating the banjo with the high class in the 1860s, their efforts to break away from banjo traditions (a.k.a. its African roots) paved the way for its future evolution. When new styles of banjo were desired 50 years later, it was easier to remove the banjo from minstrel tradition and allow it to adapt to the needs of the jazz movement. With the rise of the tango, jazz, and other dance music we also start to the see a rise of the 4 string banjo (which at this time is often referred to as a "Tango Banjo". This would eventually come to be mistakenly referred to later as the "Tenor Banjo"). The mandolin was still enjoying some popularity and we start to see more banjo-mandolin combination instruments used in dance bands. As the music grows and changes we continue to see a lot of banjo (four string), mandolin, and tenor guitar. Since these instruments all have four (courses on mandolin) of strings and were tuned in fifths, musicians found it easier to switch between them to fit whatever sound was needed. All three of these instruments (effectively. guitar and mandolin have melodic content in other contexts but that's a whole other thing), especially the banjo are still rhythm instruments. The banjo is meant to add interesting rhythmic strum patterns with crude chord melodies to songs. But as the music moves into the 1920's and more musicians are playing the banjo we see melodic content appear particularly with artists like Harry Resser. This offers a favorable musical counterpoint to the novel piano playing also popular at this time.

As jazz starts to form, we have string instruments playing with brass instruments and a competition for volume begins. Those banjos with resonators that builders were experimenting with in the 1870's start to become popular. Plectrums (flat picks) which were used to play mandolin start to be used on the banjo to increase its volume from what was possible with just fingernails. The physics of how banjos make sound made them much louder than the mandolins and guitars of this time. In addition to being louder than other similar string instruments, the cutting (piercing?) sound waves that the banjo makes made it really easy to record. recording technology at this time is still basic and the nature of the banjo makes it very useful in recording sessions. This would be somewhat short lived, though. Electronic recording equipment and microphones would soon make recording other instruments easier. Guitar companies would also soon start to manufacture bigger, louder, steel string guitars and as jazz starts to mellow out (and turns into swing) as we enter the 30's, the brash sounds of the banjo no longer fit the music. As Jazz becomes more accepted and rises in overall popularity, the use and association of the banjo in jazz fades.

While all of this was happening, people were "discovering" Appalachia, a cultural region adjacent to the mountain range of the same name in the eastern United States. Literature and fiction about this area became popular in the first two decades of the 20th century and would often use "ballads" to add a flair of authenticity to the writing, similar to the authenticity the banjo had bestowed on blackface performers. Ballads were (are) essentially songs whose lyrics told folk stories, many of which at this time had been brought to the area with the original settlers from Europe. So by the time "Cecil Sharp told the world that more old British ballads were to be found in the Southern mountains of the United States than the British Isles, middle-class Americans" were already well aware of the tradition.These ballads had been passed down as they always were; orally, generation to generation. The mountains in that region are generally pretty imposing. Anyone who has seen them could understand how before cars it was unlikely that there would not have been much mingling between towns even just a few miles apart. This discovery sparked people's imagination and led the rest of the country to believe that this contained area had preserved the traditions and culture of 18th century England in stasis. "By the 1930's an allusion to the Elizabethan quality of mountain culture had become a commonplace of popular literature." The reality of this was limited but cognitive dissonance and mental gymnastics allowed people to believe that the lower Appalachian mountains were a bastion of anglo-saxon heritage, untouched by the pragmatic hand of urban industrialization (and, at this time, black culture). This wasn't really true in any way and even though the black population in these regions varied, it was much higher than people made it out to be. As sentimentalism for this region grew, a lot of the same belittling explanations arise about the people and their culture which did not fit into the official culture of the time. We see a return of the idealistic view of the South, "our national 'Other'", and its people. "By placing them imaginatively in the past, poverty turned into pioneer simplicity and cultural isolation into Anglo-Saxon cultural survival".

Similar to when the minstrel stage heavily informed people's ideas of Southern black culture, this idea of "Appalachia as an Elizabethan museum and repository of the dominant group's folk heritage" affected actual events and music. From the book we learn that "School teachers instructed their Appalachian pupils in the art of old English sword dances and Morris dances - dances that had never existed in the mountains and their revival by folklorists in England had been more disinterment than rejuvenation. in an interview of 1934, Jean Thomas, an Appalachian "popularizer" and the creator and director of the American Folk Song Festival in Kentucky, described her opening for the festival:

You see, I open the festival with a piper walking down the mountainside playing a silver flute and followed by little Lincolnshire dancers in authentic costumes. . . and the children dance an old Lincolnshire dance that still survives in our Kentucky hills. At the back of the main stage is a semi-circle of pretty mountain girls dressed as Elizabethan ladies-in-waiting. . . . My minstrels are seated on the backless benches in front of the stage. They have their dulcimers, guitars, banjos, harmonicas and accordions. The program shows the authentic steps of America's ballad history. We aim, through song, to build up a picture of mountain life as it has been lived in these hills since the seventeenth century."

While a "revival" of an imagined culture and heritage was happening in Appalachia, music and dance that were actually traditional to the region were also being preserved and presented at festivals such as Bascom Lamar Lunsford's Asheville "Mountain Dance and Folk Festival". This festival, inspired by the tourism in Asheville threatening local culture, aimed to cater both to outside influence while preserving local music and dance.

Interest in the culture and music of Appalachia is on the rise. The banjo had of course been played in this area since its introduction to this country. At this time, however, the banjo was still very heavily associated with jazz, mass culture, and modernism. Despite its ancestry, it had gone through a lot of musical changes in the past 50 years and folklorists "traditionally prefer to study music that displayed stability (lack of historical change) and uniformity, these characteristics being accepted as signs of authenticity." The mountain dulcimer was actually considered much more traditional than the banjo despite it a german prototype. Perhaps tellingly, the dulcimer was also often associated with women and it's music was far removed from dancing. Remember that this is during a time when the high class is still feeling threatened by pop culture. Even though a lot of songs of this regions were collected, tunes (tunes don't have words), due their association with dancing were not heavily archived at this time. This new revitalized sentimental movement inspired by the growing industrialization of this time is once again focused on the South, albeit the upper mountain region rather than the lower plantations.

When bluegrass was in its formative stages, black face was still around though not nearly as popular as it had been. The birth of Jazz and highly public images of urban African American life made it hard reconcile those old beliefs presented on the vaudeville stage. Blackface did, however, find a role in newly formed country music which also played on sentimental, nostalgic family values. Even early incarnations of the Blue Grass Boys featured a black face comedian. "Comedian" is an important distinction here. throughout its history, minstrel banjo players have always played a somewhat comedic role generally at the expense of African Americans. When black face mostly disappears from country music (mostly at the insistence of record companies for fear of offending consumers), the banjo and its comedic (as well as it's anti modernistic) associations remained. While most of the racist implications that came with blackface had left it (barring some questionable song subjects), all of the same theatrical elements, sentimentalism and comedy at the expense of a disadvantaged group were still there (this is a super hard sentence to write. Just understand that while banjo comedians may portray overly stylized stereotypical versions of mountain people, the social implication is nowhere near as powerful or as damaging as blackface is. These rural mountain people and their culture was largely marginalized and taken advantage of, but this is not the place where I want to try to explain complex race relations and expressions). Early banjo players and their performance venues fit these circumstances only without the blackface. Banjo players such as Stringbean, Uncle Dave Macon or Grandpa Jones, while very talented, often portrayed overly theatrical versions of mountain folks in theatrical shows that were meant to present sentimental family values such as Hee Haw or the Grand Ol Opry.

Earl Scruggs changed all of this. When Scruggs played on the Opry with Bill Monroe in 1945 he took professional banjo playing out of the minstrel tradition. When the Grand Ol Opry's first star, Uncle Dave Macon, (a banjo player and comedian who originally gained regional popularity doing vaudeville in the 1920's) saw Scruggs play on the Opry he's quoted as saying only "he ain't one damned bit funny". But, as the book says, "Earl Scruggs did not transform the banjo only by refusing the role of minstrel, he created new musical territory for the instrument". High melodic content and playing up the neck had not really been seen before other than A.A. Farland, the elevated banjo player of the 1860s. Farland was also trying to refuse the minstrel association of professional banjo playing by playing previously unheard of complex classical music on the banjo. But (besides the 80 years worth of history) what might have made Scruggs more successful is that he offered a compromise. If the banjo didn't have to be associated with comedy, it could still be associated with sentimental, nostalgic values in the form of bluegrass music.

The banjo, however, had not earned its place in the growing folk movement yet. Folklorists continued to deny it any cultural authenticity. This idea of "cultural authenticity" is a bit strange but it does reveal the intentions of situations where outsiders try to evaluate folk cultures (the irony is not lost on me here). It's important to understand that the high class is generally at odds with popular culture. As new things become popular and threaten to change the status quo, high-class taste makers are quick to try to assert authority over these objects and devalue them for the sake of maintaining their position. In this case, we have perhaps the most authentic folk music symbol of the South being disregarded in favor of the dulcimer because of somewhat arbitrary beliefs about authenticity. "Authenticity does not reside in the object, rather it is the result of a matching set of characteristics of the object with an external claim or set of values."

"the study and use of folk culture by educated outsiders should be recognized as within the interests of high culture and its battle with the force of mass culture"

Banjo did eventually gain its place in the folk movement due in no small part to a relatively limited group of dedicated enthusiasts within the folk revival who managed to shoehorn bluegrass into folk at seemingly every possible chance. Among these fans was Pete Seeger who is a hero of the banjo himself who had become enamored with the instrument after seeing the banjo for the first time on a trip with his father to the Asheville "Mountain Dance and Folk Festival". Seeger, born in 1919, was well aware of banjo as an instrument on the jazz stage and increasingly kitchen vaudeville stage. This early experience with the five string banjo that would disassociate it from those prior connections for him. in addition to causing him to fall in love with it, seeing the banjo in the rural setting convinced Seeger of its authenticity. "for Seeger, four-string banjo had been ruined by the athletic exhibitions of commercial performers but the five string banjo exuded honesty of working class folk." As time passed, it also became increasingly easier for the five-string banjo of bluegrass and old-time music to be considered authentic as competing forms of the banjo were dying out. Vaudeville had all but disappeared and banjo in jazz was nearly nonexistent. As we enter the 1960's, rock and roll and the electric guitar now threaten both this traditional mountain music and the anti-modern values of the folk revival making them easier allies. This relationship would at the very least save bluegrass, a subversive all acoustic country sub-genre, from an otherwise almost certain demise at the hands of pop culture.

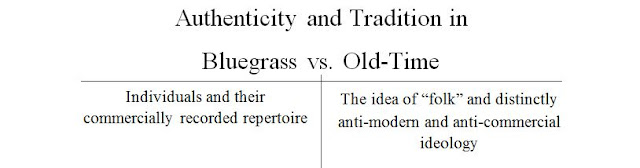

An interesting divide happens during the combination of the folk revival and bluegrass and the meeting of similar but distinct value systems. While both communities lamented the current route of pop culture and are nostalgic for the past, bluegrass was mostly patronized by older Southern conservative rural folks whereas the folk movement was created and led by young, middle-class college educated Northerners. These two groups meeting within mountain string band traditions caused (and continues to cause) some tension. More than politically, these two groups had different musical value systems that informed what they found to, once again, be "authentic".

It seems like this is the formal split between what is now called bluegrass music and what is now call old time music. At the inception of both of these "genres", the line between the two was blurred by various playing styles and creative freedom. But as time has gone on "instruction books, records, and tapes as well as contest playing have encouraged the standardization of styles within its rigid categories for marketing and competition."

As time has gone on it has been hard to define the culture of a music supported so strongly by such otherwise opposed groups. It's simply hard to reconcile the "image of Pete Seeger, always with banjo in hand, singing radical union songs with the picture of Henry Ford, patron of old-time music, advocating an American square dance revival. . . . Although their motivations were different, in the end, Pete Seeger and Henry Ford do share this much: a sentimental glorification of the American Common Man"

Today (although, again, this book was published in the early 90's but i think this still generally applies), we still see the banjo as a pretty clear symbol. In both it's "old time" and "bluegrass" forms it represents a style of music with a nostalgic view of the past. As those other previously mentioned competitors (jazz banjo, vaudeville, etc) have now more than ever been relegated to the past, the banjo now exists as a fairly unmistakable symbol. "The fiddle can be mistaken for a violin, the guitar is used in too many other kinds of music, the mandolin doesn't have a long history in this country, the dulcimer (either kind) is not very recognizable to the general public, but the five string banjo can neither be mistaken or forgotten". The iconography in our current culture is unmistakable; if you want to conjure an image of nostalgia, anti-modernism and purposeful dissent from pop culture values, the banjo is your go to symbol. Mass media in the form of movies, television and radio have further perpetuated both the nostalgic idea of the banjo as well as its theatrical and stereotypical image. Though a new wave of modern banjo usage and users such as Bela Fleck, Danny Barnes, Jens Kruger, etc (in this country and musical idiom. We'll talk about Irish tenor banjo another time) have started to try to once again create new ground for the banjo. perhaps one of them, like Scruggs will finally achieve the goal of the elevated banjo player (though hopefully without all the racism) and bring the role of the professional banjo player out of its stereotypes and into the realm of respected music.

TLDR; The banjo, an African folk instrument brought to America by African slaves, become popular in bourgeois society as an expression of nostalgia for an idealized past. When Jazz modernized the image of both African Americans and the banjo, the banjo, now only popular country music, lost its race connotations but maintained its connection to comedy and sentimentalism. Earl Scruggs would create a new era of serious professional banjo players removed from the minstrel tradition but popular media would reinforce stereotypes about hillbillies and the banjo. Today, the banjo continues to exist as a symbol of a romanticized past and counter culture trends making it desirable to a wide variety of otherwise opposed cultural groups.

Timeline

(If the timeline doesn't work, or you want to send just this, here's the link, I think. I'm still trying to figure out how it works.)

https://cdn.knightlab.com/libs/timeline3/latest/embed/index.html?source=1lkxckEk6-yz7bDn4ysw7Dv_RSnoymhxxDkh1BOiZrWY&font=Abril-DroidSans&lang=en&timenav_position=top&initial_zoom=2&height=750

Conclusions

Here are some of the conclusions I've drawn from this book as they relate to bluegrass. Overall, this blog is meant to synthesize all of this information into theories about why people feel the way they do about bluegrass. Other things will be researched to try to achieve that goal but I'll always be looking at things with an eye towards bluegrass. Now a bit of retcon, I've read some other books on all of this stuff already. This is just the first post I've made. So in this synthesis essay I'm drawing a lot from some other sources, mainly Neil Rosenberg's Bluegrass: A history which I am working on posts for. I'd like to save some of that analysis for those posts so it might seem like I'm glossing over some stuff but hopefully not too much.

This book presents evidence that, when mixed with my own life experiences, leads me to believe that the highly dedicated following of bluegrass music is partly due to and held together by idealism. The history and expressions of bluegrass in popular media are based largely on nostalgia and have linked the word "bluegrass" to anti-modernism. In many ways, it has always been the banjo that has briefly brought bluegrass music into the light of pop culture. Perhaps the history of the banjo as an anti-modern symbol has amplified this tenant of bluegrass and has contributed both to its growth and restrictions as a genre.

Without getting into the semantics of when bluegrass music started, we can pretty safely say that bluegrass, as a subgenre of country music, has always shared some of the nostalgic and theatrical elements inherent of the banjo. If we recognize "genres" to be commercial classifications that make music easier to find and market to consumers, then we can recognize that the commercial value of "country music" (or hillbilly music) lies in the reinforcement of conservative values, the glorification of rural life, and a general nostalgia for an idealized past with (less as time has gone on) various nods to tradition. When Bill Monroe started The Blue Grass Boys, country music had already moved beyond its hillbilly string band roots (like Fiddlin' Johnny Carson) thanks, essentially, to Jimmie Rodgers. In fact, part of the appeal of Monroe's band was this nod towards old time string bands. Still, whether or not its considered as such today, in the time of their creation, Bill Monroe and the Bluegrass Boys were considered a country act. By this time (late 30's/early 40's), country music had already firmly established this connection to the past in song lyrics and was now presenting the ideas a bit more blatantly in theater performances. Shows like the Grand Ol' Opry (and later Hee Haw) were meant to represent an idealized family gathering in the country and the staging often made it seem much more informal than it was. "Tent shows" were a traveling version of the same idea and when Bill Monroe puts together his own tent show, we can see that at the very least from a commercial standpoint he wanted his music to be perceived with these rose-colored glasses. From Neil Rosenberg's Bluegrass: A History

Within this communal or extended-family aggregation were smaller identifiable units. There was the brother duet, symbolizing in its very form the children of the nuclear family unit. The religious quartet reflected the close ties between church, family, and community in most of the towns where the show appeared, as well as the affirmation of coordinated small-group activities (like sports) by men. Solo singing by both male and female vocalists highlighted the personalities found in such aggregation. Fiddle tunes - often in conjunction with a show square dance set or a step dancer - reflected the role of the local fiddler, still well known as the communal provider of music for dances. Finally there was the comedian, who acted out roles familiar not only on stage but also in real life - the foolish, blackfaced, stereotyped "niggers" (who often played an instrument associated with Afro-American music, the banjo), the eccentric uncle, silly cousin, old-fashioned grandpa or the 'village idiot,' [58]Even when blackface (mercifully) effectively disappears from the country music stage, the comedian character, who often played the banjo, remained. Some of the Opry's biggest stars were banjo comedians. Uncle Dave Macon who bridged the gap between the vaudeville stage and the country stage, Dave "Stringbean" Akeman who played in the Blue Grass Boys, and Grandpa Jones who in addition to comedy would use the banjo (rather than the guitar) to symbolize a turn back towards a traditionalism and away from increasingly modern country.

When Earl Scruggs joins the Blue Grass Boys he removes the role of minstrel that had forever been tied to the banjo but keeps the sentimental feeling it provides by playing it within the context of bluegrass (not on purpose, obviously, it just worked out that way). Country music is starting to change and by 1945 Bill Monroe is thought to have a much more old time sound than a lot of the other country stars of the day. Earl's contributions to bluegrass would turn out to (very coincidentally) work in the favor of bluegrass. Comedic banjo playing, regardless of blackface, is well known and tied heavily to the commercial music industry. The role of the comedic banjo player mostly disappears but a following of people enamored by the playing of Scruggs has already begun to form and people are imitating this style; technically complex banjo playing in old time music without comedy. When country music starts to modernize, bluegrass (still yet to be named) audiences start to shrink. On the brink of destruction, bluegrass is "discovered" by the folk revival. Despite it being just as commercial as other country music, bluegrass has ties to old time traditions, refuses to modernize and has this really electrifying banjo playing with a (relatively) large number of followers. These factors, particularly the stubborn insistence (with few exceptions) to remain acoustic convinced revivalist of the folk authenticity of bluegrass (see the last 5 or so paragraphs of the review). As time went on, the association of bluegrass as a cultural maverick (or outsider. maverick is just a cooler word and implies the voluntary exile), especially within the country idiom, grew. As previously discussed, regardless of any sort of possible musical connection, the banjo is the most visually and sonically recognizably unique aspect of bluegrass. As the three finger banjo lexicon has grown to encompass far more than just bluegrass, the association has not changed. leading people to often equivocate any music with a banjo to bluegrass. Similarly, it seems that bluegrass has come to represent the idea of enduring counter-culture as popular portrayals reinforce to outsiders that it has maintained its roots and continued to remain uncommercial, whether or not that's true. in this way, we frequently see the word "bluegrass" associated to things that rather than having much to do with Bill Monroe, want to evoke a feeling of counter culture independence and we see the banjo used as a symbol of general nostalgia both within and outside of this movement.

As we start to see bluegrass appear in the media outside of country music, the banjo as the most identifiable symbol is often leading the charge and from its use and reactions we can interpret how it continues to be perceived by the public at large. There have been a variety of random appearances of bluegrass in pop culture but the really big ones are TV Shows (The Beverly Hillbillies, The Andy Griffith Show), Movies (Bonnie and Clyde, Deliverance, O' Brother Where Art Thou), and Bands (Mumford and Sons, the Avett Brothers, The Dixie Chicks, Old Crow Medicine Show, Ricky Skaggs, Alison Krauss and Union Station, Punch Brothers/Chris Thile). The imagery in the TV shows is easily recognizable. In both Flatt & Scruggs and The Dillards, bands with prominently showcased banjos, the shows express either sentimental values or mock rural lifestyle and the music helps to either reinforce those values or give authenticity to the setting. It is difficult to understate the musical precedent set by both Bonnie and Clyde and Deliverance. The popularity of Foggy Mountain Breakdown from Bonnie and Clyde (which sold better on the pop charts than the country charts) ushered in an ongoing era of heavily banjo-centric music being used in movies soundtracks, tv and radio ads and even political ads [Rosenberg p263]. Dueling Banjos has since become one of, if not, the most requested "bluegrass" songs of all time (a tenor banjo instrumental is really pushing the limits of what can be considered bluegrass for me). The Cohen Brothers film O' brother Where art Thou on the other hand, does not very prominently feature the banjo. There's a much bigger emphasis on the vocal aspect of rural music. The direction of this movie from the lighting to various folk references are meant to evoke a feeling of the past and the music, which played a major role in it's development, is meant to support this feeling of the past. The popularity of this movie's soundtrack was huge being now certified eight times platinum (and I think it actually outsold the movie itself). People were so enamored by these sounds meant to evoke images of the past that an independent concert of the musicians involved was put on and film and the musicians dubbed over the lead characters have headlined festivals under the name of the fake band from the movie, The Soggy Bottom Boys. Each one of the bands listed could have a book written about their introduction of bluegrass to a wider genre (perhaps we'll save that for another time). What might be most relevant today though, is the introduction of banjo to pop music led largely by Mumford and Sons. Mumford and Sons seem to musically try to evoke a feeling of folk music mixed with newer pop rhythms and vocal styles. Their "look" often reflects this nostalgic musical feeling and has often been mocked by people who think they're trying too hard. The point stands though (and this is anecdotal. There's evidence somewhere I'm sure but I do not have it right now) that there has been a rise in interest in bluegrass, especially amongst younger audiences, since their explosion onto the music scene.

When discussing bluegrass I think it's somewhat important to distinguish between bluegrass music and bluegrass culture. The two are obviously very closely intertwined but are distinct discussions. I think part of the issue we've been having lately is that as the world has become more globalized and the regional variations in bluegrass have begun to intersect (hey did you know people are trying to mash in Colorado? And they've been mashing in the Czech Republic for decades.) The participatory nature of this music is often what attracts people to it but navigating the social minefield of knowing what is and isn't "bluegrass" can often discourage newcomers from remaining in the community (and possibly learning what actually is and isn't bluegrass). There's disconnect between how communities have grown and how the music has grown. Soon we will be faced not just with the decision of which of the more progressive bluegrass styles to support in our communities, but which variations of traditional style to support. Bluegrass music is a small genre that is by its very nature counter culture and regressive ("with a focus on preserving tradition" for those of you who prefer euphemisms). For 50 years now the community at large has been represented both by Pete Seeger and Henry Ford. This is, like it or not, a commercial genre of music that cannot thrive as segregated micro genres of music. The progress of music and culture will never halt but people will always enjoy looking back fondly (and idealistically) on what once was. Perhaps we should take a note from Bascom Lamar Lunsford who knew that he could not contain modernization but instead catered to outsider influence while encouraging the preservation of local music and dance.

Lingering Questions

A friend of mine who is currently a history major in college offered me some encouraging words the other day; "The more you learn, the less you'll know" or something like that. Which was actually very comforting. My book hoarding started once I read Bluegrass: A History and realized there were about 100 things I felt like I didn't understand well enough to fully form opinions about the book. My list of questions grows with every piece of information but that's a good thing because maybe we're just not asking the right questions. The list of books to acquire has also grown and perhaps I'll get around to posting that eventually. Here are some of the prevailing questions I have written down after reading That Half-Barbaric Twang.

Have there been other intentional attempts to "elevate" the banjo?

[I seem to recall hearing Bela Fleck in an interview talk about wanting to prove that the banjo could be used as a serious instrument to make serious music. Also listening to people like Tom Nechville talk about the banjo sounds a lot like the banjo builders of that 1860's elevation period]

Was the florentine style of mandolins manufactured by Gibson in the early 20th century meant to appeal to the public's desire for exoticism?

How do the high, middle and low classes interact with "official" and pop culture?

[General sociology stuff. Class dynamics play a huge, seemingly unspoken role in bluegrass communities]

What are some modern examples of sentimentalism being expressed through pop culture?

[I used the example of Great Gatsby romanticism. There are also a billion terrible memes with this vibe]

What is the history of minstrelsy (and by extension, the banjo) in England and what is its relationship to the history within the United States?

What was the history of the banjo in the South prior to the creation of Jazz?

How long do societal perceptions of cultural symbols last?

[I was just so blown away when the book showed how popular representation of black banjo players had actually aged over time. Also, the lingering comedic element is intriguing but could probably be explained by the perpetuation of stereotypes in pop culture]

Do appropriated forms of art typically go through a theatrical period before they are accepted into the mainstream?

Is classical music now a sentimental form of music?

Is mash a progressive or sentimental style of bluegrass? Can it be both?

How did people get from bandurrias to mandolins?

Is the idea of "otherness" related to the idea of "lonesome"?

Who brought "up the neck" playing to clawhammer banjo and when?

Does the banjo still require a primitive setting?

[there's a part in the books where the author explains that a lot of theatrical banjo usage in the 20th century required some sort of primitive setting. With things like the the the Beverly Hillbillies, the way the musicians were dressed implies that they're coming from a primitive setting, but to play a bit of devil's advocate look at something like Avicii's Hey Brother, which I know doesn't have banjo but still uses a lot of bluegrass influence. There's no primitive setting in the music video but the song is very sentimental. So does bluegrass require a sentimental setting? And a primitive one if it's using the banjo? I don't know that's why we ask these questions!]

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

There's still more to learn. Even if we now this idea of the banjo as a symbol of sentimentalism and bluegrass as a genre held together by idealism, there are still questions of why we enjoy those sounds so much. I ragged a little bit on pre-Scruggs banjo players/comedians but all three of those clips I posted are just awesome. Perhaps the next book will reveal why this hillbilly music excites me so much. This was a fun challenge and I feel like I'm more comfortable with it already. You can subscribe below to get an email the next time a post comes out. Stay tuned for more nerdgrass!

Just finished reading your entire post. It's very interesting. It's a lot to read, to absorb, and to think about. But I did enjoy reading all of it.

ReplyDeleteI did learn a couple of things. I did know about Sweeney but I'd always read that he added the fifth string, not the fourth as you found in the book. That is a good quote from the book concerning Scruggs and how he created new musical territory for the banjo. Never thought of it in those words, but that's exactly what he did I reckon.

It is a difficult task to define what is bluegrass. I know you're gonna get to it eventually here, but the term bluegrass, today, seems to be a large umbrella that that covers many types of acoustic string music.

You seem to be doing your homework well and are doing a good job so far. Thank you for using the correct Blue Grass Boys name (not Bluegrass Boys).

I may have more thoughts at a later time after thinking this over.

Todd

Glad you enjoyed it Todd, thanks for the kind words.

DeleteHey Tristan,

ReplyDeleteI'm reading in bite-sized chunks, which I've always found to be a sensible way to consume a huge meal.

I think you might be interested in an essay called "Epic Pooh." It's essentially a scathing review of Tolkien that Michael Moorcock has been rewriting for about 40 years. In it, he accuses Tolkien and other authors of playing to old English fears regarding societal change, technological advancement, and social progress. I don't necessarily agree with everything in the essay, but it's an interesting read nonetheless. I wonder if the massive success of the authors Moorcock criticizes, whose works play to the notion of a pastoral ideal, is connected to the experience of bluegrass that you're exploring in this blog.

Best of luck with future posts. I'll be reading.

What an obscure and fantastic suggestion! My favorite kind. I'll definitely try to check it out!

DeleteHey, Tristan. I just read your post. I enjoyed it and learned a lot. Thanks! You probably don't remember, but I met you once at your home in New Mexico. I had stopped by to visit your dad who I used to hang out with in Dallas before you were born. Please tell him Mac Davies said hello and that I miss seeing him.

ReplyDeleteHey Mac,

DeleteGood to hear from you! My dad says "Hello; i miss him too".

Proving again that it's easier to write long than write short :-). It's been a long while since I read the book, so I skipped down to your conclusions and read as much as I could for now. I think you're definitely chasing down the right paths. I will point out that the "conservative" (musically speaking) aspect of early bluegrass can be overstated, and its modern aspects understated. There's a great place in Neil's book where he quotes Curly Seckler as saying, with respect to the Blue Grass Boys of 1946-47, that everyone was talking about how Bill's sound had changed, and I always thought that the place in the High Lonesome Sound movie where you (I think) first hear that band, it's "Bluegrass Breakdown" set against images of locomotives, mass production factories assembly lines and so on, makes this point in a very evocative way. So at the outset, there's definitely this modern element to it, too, and it's been a consistent thread ever since. Anyway, I need to get you hooked up with some people, my friend!

ReplyDeleteThis was condensed! Haha part of why I'm doing this was I was orginallytrying to write something for 20 minutes of talking but ended writing anhours worth. I figured if I knew the materialwell enough, I'd beable to pick what was important to talk about. We're still getting there.

DeleteI see what you're saying about Monroe and I get that. I think bluegrass (extremely frustratingly) seems to be characterized by a lot of contradictions and paradoxes. Seemingly more so than other genres.In this case, while Monroe was very self consciously rural and old fashioned, he was also innovative and insistent on a professional image that contrasted with the vibe of the opry at the time of his joining. I just wrote down this quote from Niel's book last night:

"Bill Monroe has done to Rodgers's song what Elvis Presley would later do to his 'Blue Moon of Kentucky' in 1954: he rhythmically reshaped it to fit a new genre."

I think the real contradiction doesn't come in until the 3rd generation or so where there's a boom of people playing bluegrass and with many not just specifically imitating Bill Monroe (or Earl Scruggs), but also admonishing those who were innovating and trying new things with the music. I think with Monroe, like Mumford and Sons, part of the appeal is that it was (or is) an updated, new, exciting music, that still gave this nostalgic vibe.

As a bit of a related side note, I just saw La La Land which begins to touch on this idea, only instead with Jazz, which was very exciting. Unfortunately they didn't explore it very much and the second act turned into a pretty predictable romantic conflict (but maybe I just interpreted it wrong. Cinema isn't exactly my forte). I have a variety of books on jazz and rock as well as I think some of the challenges faced by these genres could potentially reveal some of the inner workings of bluegrass.

Perhaps we'll talk more about it this weekend! :p

Great read, Tristan. I have a (lingering?) question on your use of "mash." I only have a superficial idea of its meaning since it appears to be a specialized colloquialism and was wondering if you could define it better for me and perhaps other fogies like me. Thanks.

ReplyDeleteJim

Hey Jim,

DeleteI didn't even realize I had done that haha. I'm usually pretty aware of that. I'm working on a synthesis of some different ideas about this that hopefully I'll post eventually. That'll be awhile though. For now, although I think the idea is rapidly changing, mash would most generally describe a style of play bluegrass that puts a lot more emphasis on the downbeat. The playing of individual instruments is distinct as well and can be traced back to (though not exclusively in any respect) musicians like Jimmy Martin (guitar, specifically rhythm) and Terry Baucom (banjo). There's a lot (well maybe not a lot) of debate about what and who is mash but the Lonesome River Band is pretty consistently given as an example. Hopefully I can write something about this at greater length soon! Thanks for the question, Jim.

Regarding Sweeney and the adding of a string, the bass string does appear somewhere around the 1830's when he got his start, but there is no evidence that he was the one who added it. The Half-Barbaric Twang is a good book but by no means the final word in minstrelsy studies. Two guys who really know their banjo history are Tony Thomas and Greg Adams, you can find them on Facebook. Just my 2 cents

ReplyDeleteCarl Anderton

I replied before but this site doesn't seem to let you edit comments, which is a bummer for someone like me who makes a lot of typos. What I said was: Thanks for the tip, Carl. I was fairly suspicious of the idea that Sweeney had added it. The book expresses a similar sentiment but does generally imply that he was one of the first guys publicly playing a 5 string banjo. It was 1991 so the proof that he didn't invent the high 5th string might have been shocking enough of a fact for people. I'll check those guys out though. Thanks for your thoughts!

DeleteThis comment has been removed by the author.

ReplyDeleteTristan,

ReplyDeleteI don't think you need 'have trouble with' the final part ('Conclusion: Sentimental banjos') of Karen Linn's book, where (in your words) she 'talks about a personal experience at a Smithsonian Folkways festival where she takes some of the borderline offensive and appropriating shows of a folk-based old time festival, and ties the blame in with bluegrass. No one is playing bones on stage at a bluegrass festival.'

Look at the piece again: the performers concerned are specifically identified as 'an Old-Time music group', trying to be faithful to 'the Southern mountain tradition'. There's nothing in that paragraph to link this to bluegrass; indeed, the paragraph immediately following it stresses the separation between old-time and bluegrass players in style and repertoire, and their 'self-segregation' into different jams at the festival. I don't personally feel that Linn expresses or implies any blame at the playing of material from the minstrel era, though she does admit to feeling 'unnerved' on that occasion.

Finally, thanks again to you, your father, and the rest of the band for the magnificent shows in your tour of Ireland a year ago. I've put a post about 'The Why Lonesome Sound' on my own 'Bluegrass Ireland Blog' today. All the best,

Richard Hawkins

Good to hear from you Richard. Yes, I think you're right. In retrospect, those thoughts seem a bit clunky on my part. I don't have the book in front of me at the moment (as I've lent it to a friend) but from what I remember, I believe my feeling was that she was taking the unnerving feelings of that experience and applying them to the banjo as an instrument and while it wasn't a bluegrass festival, it just felt like a bit of a broad generalization. Still, i think the jump to bluegrass might have just been due to sensitivity on my part.

DeleteThanks for the write up, I really appreciate it and I'm hoping we'll see you next month when we're back in Ireland.

Take care!

Great article, really well-researched and thorough!

ReplyDeleteThe timeline is amazing, Tristan. Well done!!! One book that I think you would enjoy is A Free State, by Tom Piazza. It deals with minstrelsy and the banjo, pre-Civil War. Excellent writing, and Tom is also the author of an incredible essay about Jimmy Martin, which is in his collection Devil Sent the Rain. I know; just what you need -- more to read. I'm looking forward to reading the next installment!

ReplyDeleteI have read your article and liked it. Some thoughts about the book you write about came up: for instance: is the situation regarding to Bluegrass so much changed since publication that a lot of it seems not accurate anymore? You talk about sentimental, rural and nostalgic, but when I look back now there are parts in the history of the banjo that were not nostalgic at all.

ReplyDelete- When Monroe started he didn't act a nostalgic hillbilly ; he dressed his group more like gentlemen-landowners of that period in 'horse trousers' (how do you call those trousers with wide thighs?) and with panama hats on. The Early Blue Grass Boys in the early fifties had this short neck ties and high up trousers; just like the fashion of the day.

The people of the classic banjo period were dressed like concert musicians of that time ( nowadays concert musicians dressed like that are an anachronism like if they are to receive the Nobel price). They didn't act nostalgic or rural, they were serious musicians, they liked the banjo and played it the way people did other things as well, just in there common days or special days clothes. The tutors of this period were classic teachers like all teachers were ; there was no acting or reenacting or nostalgic thing in it.

With this in mind I try to answer your question:

Was the florentine style of mandolins manufactured by Gibson in the early 20th century meant to appeal to the public's desire for exoticism?

My teacher at the Art Academy in Art history classes in the early seventies suggested that the Gibson mandolines from Loar werd designed according the fashion of the period: JUGENDSTIL. ( art nouveau) The architectural and design fashion of Paris, Vienna and Prague from the turn of the century was even recognizable in the US in the Gibson mandolins. Those mandolins were exceptional modern at that moment in time. The players of the classical period mandolinists and banjoists, the protagonists and builders ( Stewart) were trying to be modern and elevate the banjo. They were not trying to be nostalgic, rural. Perhaps they were sentimental though.

Ad van Trier, Doorn , the Netherlands

Great point! Let me clarify a bit.

DeleteThis book is a bit outdated but i don't think that the theories are incorrect. Perhaps I've done a disservice to the book in my synopsis but reading it, I did have to keep reminding myself that is was very specifically about the banjo in American pop culture. The banjo as a cultural symbol had different value in different regions overtime and this book is examining the banjo's various forays into the pop culture eye.

Bill Monroe was very specifically avoiding the rural stereotype associated with the banjo and, as mentioned, Earl Scruggs very specifically removed some of that nostalgic role that was historically tied to the banjo. You're right, Bill didn't have a banjo in his band because he thought it was nostalgic and Earl Scruggs didn't play it because he found it sentimental. But the commercial success of country music and bluegrass is tied to the fact that the audience found it nostalgic.

That word paints a broad stroke but for a lot of people, the banjo and the bluegrass style of music was a nostalgic reminder of their homes and heritage. And in pop culture, it represented that mythic Utopian past of the Old South. Scruggs may have removed the more vaudevillian aspects of this but his banjo contemporaries very much actively practiced this. Dave Macon was a vaudevillian star before he played on the Opry and shows before and after the Opry all the way up until now have used these sentimental stereotypes to communicate a set of antimodernistic values. This is why I don't think its an outdated idea. The book was published in 1991 and O' Brother Where Art Thou? came out in 2000. That film doesn't play on the sound of the banjo too heavily but recent inde rock trends have used the banjo to communicate a more old timey sound. The banjo is consistently related to and often can only be discussed in the context of a rural, historic setting. Even when someone does something modern on the banjo it is contrasted with the more old timey sounds of "traditional" banjo music.

A lot of this comes from the folk revival. When Pete Seeger first hears five string banjo (from Samantha Bumgarner, in North Carolina, in the 30's), he would have already been well aware of the tenor banjo due to its waning popularity in jazz music. He felt like the commercial implications of the time invalidated it as a folk instrument and felt like the playing of more rural folks like Samantha Bumgarner and later Earl Scruggs were more authentically folk. Part of this was because bluegrass, despite its original innovative nature, very stubbornly refused to electrify and folkies in the 60's saw this, the nostalgic nature of the songs (going back to the old home, memories of mother and dad, old home place, etc.), and the general old timey sound (ancient tones) as in line with their values of preserving old, more rural folk cultures. Alan Lomax did, very specifically, call for the imitation of not only musical style but regional dialect in the recreation of folk music, including bluegrass. The New Lost City Ramblers were imitating and a lot of people today are imitating (there's a lot of folks in California singing with some very fake Southern accents) those more authentic sounds was a way of expressing a values system in a similar (but not at all the same) way that blackface, made more "authentic" by the use of the banjo expressed nostalgic values about the prewar south

Even today, we can not escape the label of antimodernism (though that's not entirely unreasonable. We are closely imitating a nearly 100 year old art form).

I don't mean to minimize the innovations of Monroe and Scruggs. But the continued label of the banjo in the pubic eye as nostalgic despite various advances over the years kind of proves my point.

As for the mandolin, that's very interesting! I just finished reading some stuff about Gibson and its made that make more sense. Orville Gibson was trying to modernize the mandolin and his design aesthetics were obviously very creative. Stewart was definitely not trying to be nostalgic and I'll admit to using 'nostalgic' and 'sentimental' as more interchangeably than they are. But, once again, it's important to consider that while Stewart himself was taking a very modernist approach to the banjo, a lot of the implications of the people learning and performing on the banjo were not thinking of it as modern. The banjo, during it's pop music fad, was still associated with a romanticism that faded once black musicians began to more frequently use the banjo to create jazz and other highly popular music that threatened the cultural values of the high class. The book certainly explains this better than I could though.

DeleteI spend a fair amount of time in the Netherlands actually and will be there next in March. perhaps we'll get the chance to meet, talk some more, and maybe play a tune. if not this time then maybe the next.

Thanks for the comment!

First : is it possible in this site to use a more book page frame; with shorter lines , more white in between the lines and a bigger type? It would make reading more comfortable.

DeleteNext : through your answers plays all the time the distinction or gap between the intentions of the creating musician and the reception of the public. For instance ; I make up this myself: when The Kruger Brothers play The Appalachian Concert with a classic setting and a violin quartet they may sometimes have to deal with organizing committees or venue owners who dress up even a church as a barn with haystacks and agricultural gear. And the problem is even bigger; some artists themselves come at the stage in an outfit that make them Rinestone cowboys, which is in Europe the more outplaced. And there is the problem of imitating dialect: should we in Europe sing in English or in Dutch or Czech? The conclusions of HLSBS (b.t.w. I'm in it at page 14) indicate the non American, at least the Dutchmen just loved the music of the banjo, which probably takes off a heavy load of ballast.

Anyway the gap between musician intentions and the public's reception makes the discussion of what bluegrass might be rather difficult.

I have recently read The Banjo from Laurent Dubois a book which places the banjo in a historic context that goes back on slavery times and probably it fills the twenty year gap in banjoscience between the book you wrote about and the moment we' ve arrived today.

Though I only depend on your resume I think a big part of the 'sentimental' look in The Half Barbaric Twang specially comes from the Folk period, the period in which people started to imitate from recordings.

Bluegrass has changed over the years and we saw recently There Goodbye Girls on their Europe tour. They were affiched as Bluegrass, but the banjo played a developed style of melodic drop thumb, down picking anyway, which would name the music twenty years ago definitely as oldtime.

With this in mind we probably must leave oldtime /bluegrass discussions for finger/down picking differences. I 'm trying to think of more technically definitions and descriptions to pin down bluegrass. When I have found a result I'll let you know.

Let me know where and when I can meet you when in my country.

Thank for your reactions.

Its an interesting question because we can, to some extent, define bluegrass stylistically. Though mostly only looking to the past, We can say what defined each period of bluegrass and how it grew into the next but its hard to put qualifiers on what is bluegrass today.

DeleteI've played all over this country (and a bit in yours) and the way people experience and think about bluegrass can be strikingly different even within the same region. Some people take it very seriously and either try to make it progress or try to preserve the older sounds. for other people, its just an activity that expresses this idea of being purposefully different or antimodern.

Cool that you're in HLBS. I had found your music online when you originally commented and knew that you knew what you were talking about. Loes and her work are part of what inspired my project. The fact that people in the Netherlands could really just love the sounds of this slightly random and obscure style of american folk music is very intriguing. but I've also played in Germany where there were people who for sure only enjoyed it because of its association to america (and old america specifically). So it multifaceted.

I assume you saw the Goodbye Girls as part of the bluegrass jamboree and not to be overly pedantic but the jamboree is marketed as bluegrass and americana. This year they have a progressive bluegrass band, a singer songwriter group, and an old time string band. The Goodbye Girls are a self described string band and as much as they are related to being a bluegrass band, i wouldn't really call them a bluegrass band, though the argument could certainly be made. Monroe had plenty of frailing banjo in his band before Scruggs came around.

You're right; but Americana as a definition just widens. You also can say it is 'human' music. Of course. It is exactly the 'problem' of describing the Good Bye Girls wether they are a bluegrass group or something else combined with the different kind of receptions of many audiences that is your and mine issue. May be it is the point to find a definition which contains these differences. What you and I look for is not widening the definition but of closing in the style, to come to the skeleton that is the kernel in all varieties.

ReplyDeleteThat is what I look for as I mentioned. The idea is rudimentary yet; I let you know when I have it 'on paper'.

Ad

Tristan,

ReplyDeleteLike I promised you I wrote a definition of Bluegrass music and I added a an answer to your question Why? It was necessary to write two résumés in English to the articles about the fifth string too. It seems also to be inevitable to rewrite the articles in English which will take some time. I hope to finish them this spring. Since these writings contain original and innovative opinions of mine I think it is appropriate to publish them at my own website. You may find all these writings at www.advantrier.nl

I looked once more through your Timeline which I think is marvellous. I think it must be possible to fill in lacks to complete it. The recent book The Banjo from Laurent Dubois offers sightings of banjos (or actually banzas) before 1800. And maybe with some help of you father it is even possible to fill in the space after 1945.

By the way : last Tuesday evening we enjoyed the Chatham County Line and Mandolin Orange here in Utrecht.

I hope you enjoy reading my articles,

Ad

Hi Tristan,

ReplyDeleteI have been busy translation my original essays. I added them to my website, so now you may find next list at:

www.advantrier.nl page BANJOLOGIE

2014 Rammelen in een theeglas

2017 Ticking in a teaglass - résumé in English

2017 Ticking in a teaglass - translation in English

2016 De vijfde snaar als strijdkreet

2017 Battlecry - résumé in English

2017 Battlecry - translation in English

2017 A definition of Bluegrass

2017 Why? An answer for Tristan

2017 The Banjo from Laurent Dubois

Of course the translations and the essay written in English are for you most interesting. However I hope it will be possible for you to understand my writings.

The most important part in my view deals with what I called CLB. I introduce this 'backbone' of bluegrass in the résumé and in the translation of Battlecry. This is a complete different approach to bluegrass compared to the way you writes in you blog about the preservation of Bluegrass. I hope you will appreciate it though,

Ad van Trier